Henderson native Jaquell Sneed-Adams will be returning to her hometown to teach after she graduates from Harvard this spring.

Jaquell Sneed-Adams couldn’t have imagined when she was growing up in Vance County that she would eventually gain admission to one of the most selective colleges in the country.

The 21-year-old Northern Vance High School alumna and Henderson native will graduate from Harvard University in May and return home as a Teach for America corps member in fall 2014.

“When I was in third grade, or fifth grade, or even high school, I didn’t believe I would go to an Ivy League school,” Sneed-Adams said. “It wasn’t even in my mindset, no matter how well I was doing in school, it just didn’t seem like a possibility. Not to say there is anything wrong with going to Carolina or State, but that is the limit of what you see. I think for some people, they don’t even see the Ivy League or even going out of the state as a possibility.”

Her journey from Vance County to Cambridge, Mass., has inspired Sneed-Adams to embark on a career that helps prepare low-income students for higher education, a goal that can seem elusive for many students in Vance County, but one that she embodies.

At Northern Vance, Sneed-Adams was top of her class in academics and participated in a range of activities, from senior class president to track and field and the National Honors Society.

But, during her freshman year at Harvard, she faced an entirely new peer group and set of challenges.

“I definitely feel like I came in a lot less prepared than others,” she said. “It became really obvious to me when I came in freshman year because it was really hard coming from being at the top and then walking into a situation where you actually feel like you do not know what is going on. I had never

walked into a classroom and not known what was going on. I actually felt hopeless sometimes.”

This feeling resonated particularly strong when she took a biochemistry class required for all pre-med students.

She hadn’t taken any advanced placement science classes at Northern Vance. The school didn’t offer them.

“I was walking into a classroom where people had taken AP biology or chemistry or who went to a specialized science school,” she said. “For some people, this was a review.”

Sneed-Adams recalls feeling extremely stressed and staying up until the early hours of the morning trying to understand the material with the help of a friend.

“A lot of my experience being ill-prepared is exactly why I want to work into education,” she said. “The most prepared I felt were the courses in which my teachers went above and beyond just getting students to pass standardized tests because it takes so much more than that to succeed at these higher-level universities. There is a different mindset at these schools. They focus on exploratory learning and problem solving in a way that passing a test just doesn’t teach you.”

And then there were certain practices she had to learn for the first time, unlike many of her peers.

“A large part of it was not knowing random things that I felt like everyone else in the school knew, like how to schedule office hours, or how to talk to professors after school,” she said. “Just day-to-day things, like I had never made a resume before. Just things that I felt like some of my friends here had been doing since they were in sixth grade.”

Despite the initial academic challenges, Sneed-Adams joined a handful of student organizations and found a supportive group of friends early on, a lot of whom came from low-income communities as she did.

She joined the Black Students Association, the Association of Black Harvard Women and the cheerleading squad, among others.

She entered freshman year as a psychology major set on pre-med, but realized by her sophomore year that it wasn’t meant for her.

“I had this idea that you go off to Harvard and you go into law, medicine or business,” she said. “I realized early on the idea of pre-med did not come from what I wanted to do, but from what I thought I should be doing.”

She did research in developmental psychology during her sophomore year and enjoyed it, but the work didn’t seem like a fitting career for her.

It wasn’t until she ran into a friend, who was a Teach for America representative on campus, that she started thinking seriously about the program.

Since then, she has spent her summers working with at-risk youth in low-income communities, at home and in Cambridge.

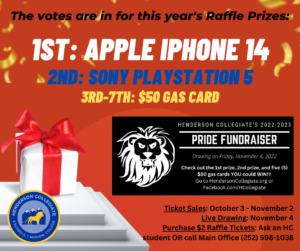

In 2011, she taught rising fifth-graders math during Henderson Collegiate’s summer program and the next summer she was mentor at the Crimson Summer Academy, a premier college prep program for low-income high school students on Harvard’s campus.

Sneed-Adams has a unique perspective as someone who came from a place similar to many of the high school students she mentors.

“Being a part of something like that makes you feel like you’re really making a positive impact on the future,” she wrote in an email. “Providing them with mentoring that I was fortunate enough to have had unofficially, but that so many young people in our situations are not fortunate enough to have, is an amazing thing.”

If all goes well, she will work with middle school students at Henderson Collegiate, through Teach for America, next school year.

She wants those students to recognize they can strive for and achieve any lofty goal, regardless of their zip code.

“How can you work towards something that you don’t know exists? College is possible. I’m not some magical person who was able to throw some spells around. This is possible. It really is.”

Contact the writer at smansur@hendersondispatch.com.