Partners for Developing Futures targets minority-led public charters

Article courtesy of Dan Way, contributor of Carolina Journal Online

HENDERSON — Statistical charts, goal-tracking graphs, and high-achiever lists line the kaleidoscopic walls at Henderson Collegiate Charter School. It was the assigned task of Taimya Scott and Carlos Cruz to interpret all that data for a visitor on Monday.

At one station, labeled “paychecks,” Scott explained the point-earning procedure to get on the list, where her name was right at the top.

“Paycheck is when you demonstrate our values, and our values are passion, integrity, achievement, community and knowledge,” she said of the minority-led, Vance County charter school whose former traditional public school students are 83 percent African American, 12 percent Latino and 5 percent white. Eighty-seven percent are on free and reduced lunches.

With their impressive command of the school rules, goals and foundational principles, the student tour guides sounded more like recruiters at a Rotary Club meeting than 10-year-old fifth-graders.

“In my old school, the teachers didn’t really care if we learned or if someone fell asleep at their desks. Here the teachers push us to learn and to do our best,” Scott said.

“At Henderson Collegiate, growth is the most important thing,” Cruz said, and in just its second year of operation, the charter school already has raised proficiencies dramatically in reading and math and has been named by the state as a school of distinction and high growth.

That is precisely the outcome Partners for Developing Futures believes is possible with exemplary, minority-led charter schools. Partners, a social investment venture fund, provides seed capital and strategic support in the creation and early stages of operation. The fund does not provide money for construction or capital improvements.

The fund, supported financially by the Walton Family and Bill and Melinda Gates foundations, is an outgrowth of the National Alliance for Public Charter Schools, whose Diversity Task Force found the need for more minority charters and minority charter school leaders.

Ref Rodriguez, president and CEO of the Los Angeles-based nonprofit, which launched in 2008, believes North Carolina is a bellwether state for the movement to enhance academic performance among underserved minority children.

Partners for Developing Futures has teamed with Raleigh-based Parents for Educational Freedom in North Carolina, a nonprofit organization advocating school choice. PEFNC was a key player in lobbying the General Assembly to eliminate the cap on the number of charter schools allowed in the state. Together, the organizations are working to identify high-quality leaders with strong community backing and solid plans for start-up charter schools run by minorities.

More than 600 educators, community leaders, lawyers and parents — three times the expected turnout — attended information sessions in Raleigh, Wilmington, Winston Salem/Greensboro, and Charlotte in September to learn how to obtain start-up funding and guidance.

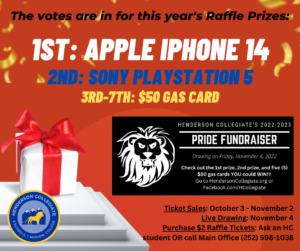

![screen_4eb18cc2394af[1]](https://hendersoncollegiate.org/wp-content/uploads/2015/07/screen_4eb18cc2394af1-300x209.jpg)

Carlos Cruz, left, and Taimya Scott, both President’s List students at Henderson Collegiate Charter School, say their teachers have high expectations of them and teach them with innovative techniques that their former traditional public school teachers di

“I thought if we got 25 we were doing a good thing,” Rodriguez said of the number of applicants who filed by the Oct. 15 deadline. “The fact that we got 87 applications from just one state is mind-blowing.” The organization received only 68 applications nationally the past two years combined.

“I think that there is a deep desire to do something different and that there is . . . a long history of leaders of color getting schools started” in North Carolina, Rodriguez said.

Partners for Developing Futures is meticulous in choosing schools to work with. The 87 applicants will be culled to five or so, from which one or two may receive start-up funding, Rodriguez said. Unsuccessful applicants can reapply as well as network with Partners staff on best practices.

Funding and insufficient financial accountability, poor organizational structure, weak leaders, and lack of community support often are the reasons behind failed charter schools, Rodriguez said. Those are the areas for which his organization provides mentoring and funding.

Of North Carolina’s 33 public charter schools shut down since 1996, “almost 40 percent of them were minority-led,” and failed for the same reasons Rodriguez cited, said Darrell Allison, PEFNC’s executive director.

Community support is key to successful charters.

“Parents’ responsibility and engagement is something that is no longer appreciated in some of our traditional public schools, and charter schools serve as a model of how you do that in a real, authentic way,” Rodriguez said.

“I believe charter schools are not the panacea but they are a real viable alternative to learn from,” Rodriguez said.” “I do believe that over time our traditional public schools have become entrenched in what isn’t possible instead of what is possible.”

If traditional schools “don’t want to change and reform, parents can use their voice and their feet to demand what is rightfully theirs,” he said. “The state and the district are in trust of the assets that belong to the community, that is the dollars and the children.”

“Make no mistake about it,” Allison said. “We’re at a devastating level here, a crisis level here, when you’re talking about children of color” and the public schools achievement gap.

Citing state Department of Public Instruction data, he said the achievement gap between white students and students of color was 24 percent in 2001.

“We had millions of dollars going to reducing the achievement gap. We came up with all these new names, new programs,” but didn’t correct core weaknesses, Allison said.

“You fast track to 2010 and . . . not only did that achievement gap remain, but it actually increased 4 additional percentage points to 28 percent. Low-income students, despite all that we’ve been trying to do over the last 20 years, are not getting better, they’re getting worse,” he said.

“This is not an endeavor just to have minorities starting mediocre public charter schools,” Allison said. Rather, excellence is the goal. “We need to be on the forefront of shutting them down” when they are not successful.

Only 47 North Carolina counties have charter schools.

“We want to make sure all children, particularly in those 53 counties that don’t have a public charter school, have one as well,” Allison said.

Joel Medley, director of the Office of Charter Schools in the state Department of Public Instruction, said Allison advised him of the push to open more exemplary minority charter schools, and that the state’s rigorous review process looks at many of the same areas Partners for Developing Futures emphasizes in its funding decisions.

State fast-track applications for new charter schools are due Nov. 10, while Rodriguez said his organization won’t make its final selections until the spring or later.

“Once the cap was lifted, we received an innumerable amount of phone calls asking for information,” Medley said. With 30,000 students on charter school waiting lists, “We could have significant numbers” of applicants.

His office will check applications for completeness, and forward them to the newly created North Carolina Public Charter School Advisory Council. The council will score them in December, interview candidates and make recommendations to the State Board of Education. The board would make a final decision in February, but no later than March, Medley said.

Allison believes a high-flying charter school can rejuvenate a downtrodden community by instilling pride and attracting businesses. He cited the entrepreneurial spirit and business skill sets at Henderson Collegiate as a “fine example” of “what we want to replicate” in a startup minority charter school.

Eric Sanchez, principal and co-founder of Henderson Collegiate, said he already is seeing signs of community pride among parents. In its first year, the charter was named by the state as a school of distinction and a school of high growth.

Students’ average end-of-grade reading test scores improved 9.95 points in the first year the school was open, and average math scores jumped 8.17 points. The state considers 4 or 5 points strong growth on EOGs. Students went from 46 percent proficient in reading to 77 percent, and from 70 to 90 percent proficient in math.

Sanchez said the goal is to add one grade per year until the school goes through 12th grade.

“We plan to be here for one more school year. Our board of directors and myself are actively pursuing a new school building,” Sanchez said. “One of the more promising possibilities” is an 86,000-square-foot tobacco warehouse being renovated into a business and community center called the REEF Project in downtown Henderson.

Dan Way is a contributor to Carolina Journal.